In 1800, John Brickwood owned all the land in the ECCO area outside Croydon Common. Because he was a wealthy man, there are many documents in public record offices that mention him. Some of them have been consulted in bringing together this account of his life. Many others have not and their contents may well alter the narrative below.

Brickwood was a merchant, colonial agent and banker. As a London member of the Company of Merchants Trading to Africa he was involved in the trade in enslaved people. He was also a prime mover in the enclosure of publicly accessible common land in Croydon. He was a bit of a chancer, misrepresenting his expenses on a government initiative and massively overestimating the value of his estate. However, he also helped Joseph Banks get specimens for Kew Gardens and helped the colonisers of Canada develop a lucrative hemp industry.

No image of John Brickwood has yet been discovered, although one of him on his horse was left in his will to his close friend, John Grantham. The latter is likely to be the civil engineer of that name who had helped make a plan of the route of the Croydon Canal in 1811. However, he is best known as the surveyor of the Shannon Navigation inland waterway. It is possible that Brickwood’s portrait may still belong to one of Grantham’s family. It would also be good to know whether the model of his cow “Empress” is still in the possession of the heirs of John Timothy Swainson of Liverpool, one of the seven founding members of the Linnean Society.

John Brickwood’s will can be viewed on The Public Records Office website https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/D153945. A transcript was attempted, then revised with consummate skill by Kake Pugh and Brenda Hawkins

Many thanks for their help to the staff of the Public Records Office, London Metropolitan Archive, Surrey Records Office, Kew Gardens Archives, Lambeth Palace Record Office and Croydon Archives. All Saints Church kindly provided some valuable information about the Brickwood memorials within, Brenda Hawkins better data about Brickwood’s birth & family, Kake Pugh evidence of Brickwood’s ownership of land in Croydon as early as 1791 and Tony Skrzypczyk some much needed images.

This account has been divided into three sections

John Brickwood’s life before Croydon

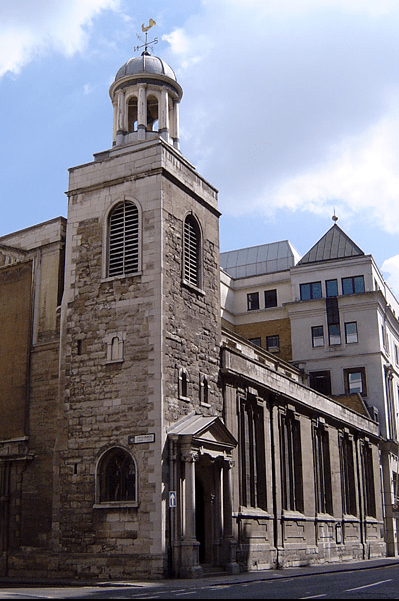

John Brickwood was born in 1743, the eldest son of John Brickwood and his wife Elizabeth (neé Desborough). He was baptised in the church of St John the Baptist, Sibson cum Stibbington, Huntingdonshire, as were his younger brothers Latham and Nathaniel. By the time John was 21, he was living in the parish of St Catherine Creechurch in the City of London. He married Judith Millington there in the summer of 1765.

St Catherine’s Creechurch, Leadenhall Street, City of London (Wikipedia)

By 1783, John Brickwood had sufficient wealth to buy a country house in south Lambeth, near Vauxhall. This was insured for £3200 (about £604,600 today) and the grounds included a brewhouse, green house, stable and coach house. The following year, he was appointed a colonial agent for Bermuda. Based in London, he was paid by the Bermudan government to represent them to the British government. Bermuda was one of the first colonies to use enslaved people for labour. As colonial agent, Brickwood represented the needs of their masters. His main role appears to have been to pass on correspondence from the government of Bermuda to the relevant officials in the British government and chase them for action. These included such people such William Wyndham Grenville, the Home Secretary. Much of the correspondence was to do with the government of the Bahamas interfering the gathering of salt by the people of Bermuda from ponds on the Turks islands. It would not have been the British settlers that would gathered the salt, but the enslaved people who they owned. An account of how they suffered when doing so can be read in The History of Mary Prince, a West Indian Slave, the first autobiography of an enslaved African women to be published (in 1831).

“I was given a half barrel and a shovel, and had to stand up to my knees in the water, from four o’clock in the morning till nine, when we were given some Indian corn boiled in water, which we were obliged to swallow as fast as we could for fear the rain should come on and melt the salt. We were then called again to our tasks, and worked through the heat of the day; the sun flaming upon our heads like fire, and raising salt blisters in those parts which were not completely covered. Our feet and legs, from standing in the salt water for so many hours, soon became full of dreadful boils, which eat down in some cases to the very bone, afflicting the sufferers with great torment. We came home at twelve; ate our corn soup, called blawly, as fast as we could, and went back to our employment till dark at night. We then shovelled up the salt in large heaps, and went down to the sea, where we washed the pickle from our limbs, and cleaned the barrows and shovels from the salt. When we returned to the house, our master gave us each our allowance of raw Indian corn, which we pounded in a mortar and boiled in water for our suppers.”

Map (Hyde 1982) showing some of the locations associated with John Brickwood including (from left)

- Lyme (Lime) Street: where the offices of Brickwood, Pattles & Co were located in Riches Court

- St Mary Axe (leading north from Lime Steet): where he had a house in 1783 and stored goods in a warehouse in 1786

- Billiter Square: where Brickwood had a house from at least 1797

- St Catherine Cree Church, Leaden Hall Street: where he married Judith Millington in 1765

- African House, Leadenhall Street: home of the African Company of Merchants to which Brickwood belonged in 1787

In 1786 John Brickwood & Thomas Pattle were listed as merchants of Riches Court, Lime Street, when they insured goods valued up to £1,000 in a warehouse in St Mary’s Axe (£194,000 today). The following year, joined by John’s youngest brother Lawrence, they insured goods valued up to £10,000 and £20,000 at warehouses in Bow Lane. The same year, John and his brother Nathaniel were listed as London members of the Company of Merchants Trading to Africa. This company was not allowed to trade in enslaved people itself, but staffed and maintained the forts on the Gold Coast and the Gambia that helped English traders to do so. Brickwood and his brother may have provided supplies to the forts (food, ammunition, building materials, medicines) and goods to be traded to the African people living around the forts (to pay for labour, fresh food & building) or to be given to those of importance to maintain good relations. The items most largely in demand by the Africans were rum, brandy, woolen & cotton materials, firearms and gunpowder. The ships that carried these goods also carried new recruits to work in the forts and orders for the governor.

On 14 May 1790, Brickwood & Pattle were among a group of merchants trading with the Bahamas Islands who stated their concern to Grenville for the safety of their property in case of “an actual rupture” with Spain. “The cotton plantations on the islands have been very successful, and the plantations are now furnished with a great number of slaves. The crop of cotton is estimated at 600 tons”.

Life before Croydon sources

- Public Records Office MS C 13/2174 34

- Findmypast website accessed 30 August 2023

- Ancestry.com website accessed 30 August 2023

- London Metropolitan Archives MS 11936/314/480731

- London Metropolitan Archives MS 11936/329/504658

- Public Record Office MS CO 37/42 1789 – 1790 no213

- The History of Mary Prince, a West Indian Slave 1831 https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/prince/prince.html retrieved August 2023

- Hyde, R., 1982. The A-Z of Georgian London. Lympney Castle, Kent: Guildhall Library London. London Topgraphical Society Publication 126.

- London Metropolitan Archives MS 11936/337/517921

- London Metropolitan Archives MS 11936/347/538141 & 11936/340/25026

- Public Record Office MS 37/42 1789 – 1790 (217)

- Historic price calculator https://www.in2013dollars.com/uk/inflation/1783

- Creighton, S., 2017. Croydon’s connections with the British slavery business, Proceedings of the Croydon Natural History and Scientific Society 20/1, 12-45.

- Penson, L., 1924. Colonial Agents of the British West Indies. University of London Press: London.

- Public Record Office MS TS 24/5 p 135 – 145.

- Public Record Office T70/1508

- The African Company of Merchants https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/African_Company_of_Merchants

- African House https://www.grubstreetproject.net/places/17/

- Martin, E. C., January 1922. The English establishments on the Gold Coast in the second half of the eighteenth century. Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 121:167-208

John Brickwood’s life in Croydon

“The Seat of John Brickwood” 1805 by John Hassell.

In 1788 John Brickwood was noted as the tenant of Broomfield in Croydon, a field just across Addiscombe Lane from where The Cricketers is today. Two years later he owned so much land in the area that he had to pay £55 tax on it a year (£10,764 today). On 4 March 1791, John Brickfield bought the right to the tithes of “lands & premises bounded by Addiscombe Land on the East, by Coney Lane on the West, by Croydon Common on the North, and by Addiscombe Lane on the South, the whole of which… contains 49 acres” for £303 13/6d (£57,252 today). By then he already owned over 19 acres of meadow and arable land within that area, but may have already set his sights on buying the rest.

However his business was still centred on the City of London. Brickwood, Pattle & Co lent money to French plantation owners living in London, fugitives from the French revolution. The loans were secured on the title deeds of their plantations. The émigrés were expecting large annual profits from their estates, based on the labour of their enslaved people, to pay back the merchants. In 1793, owners of plantations in the colony of St Domingue (Haiti) persuaded the British government to send troops to conquer the French colony. The following year, the French government, under pressure from black leaders such as Toussaint Louverture, freed all their enslaved people and these plantations could no longer turn a profit. Both the émigrés and the British merchants pressed the British government to continue in their campaign, in the hope of reinstating slavery (still legal in the British empire) and thus making good their losses. However, in 1798, the British troops signed a treaty with Louverture, now leader of St Dominique, and withdrew completely from the island. The title deeds were no longer valid and firms, such as Brickwood, Pattle & Co made substantial losses.

Some of the company’s trade was also on behalf of the British government. From 1792-93, it was paid by the British government to ship goods to Bermuda for the army. In 1795, Brickwood was authorised by the British government to buy as much wheat as possible in Canada and transport it. An embargo prevented him from shipping all of it, leaving four of the 56 vessels he had hired empty. He filled these with goods to trade on his own account. As a result, Brickwood’s expenses were £19,088 (about £3 million today) less than the amount he was paid by the government. When they eventually asked for the money back in 1809, he paid them within two days, but they then demanded that he should pay interest on this amount. Brickwood argues that he had paid £118,000 (about £17.5 million today) out of his own pocket for the wheat in the first place and that the government had been late in repaying him. He, himself, had never received any remuneration for his considerable efforts on behalf of the government. In the end, they agreed it would not be reasonable to charge him the interest.

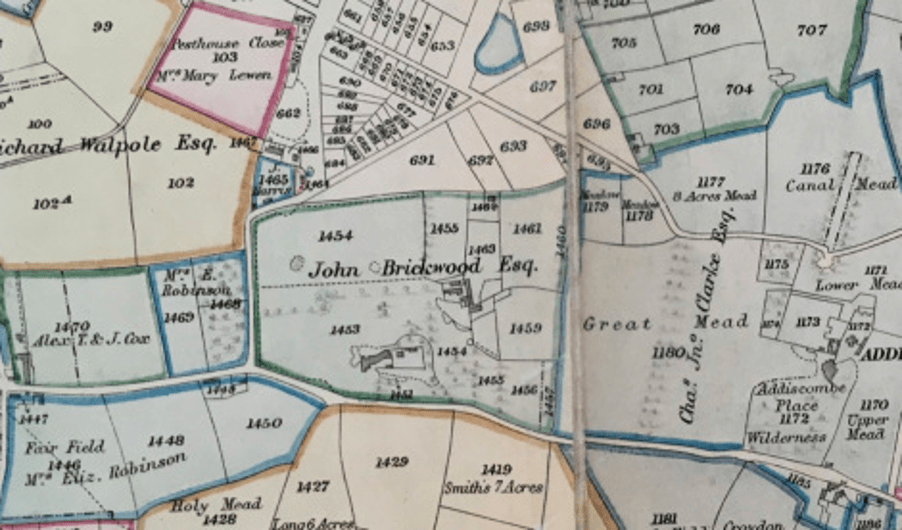

In the late 1790s, Brickwood built a large house to the north of Addiscombe Lane (now Addiscombe Road) “enclosed in a park tastefully planted with forest and other trees”. In 1796, he was one of the people who petitioned parliament for leave to introduce a private bill to enclose common land in the parish of Croydon. The poor of Croydon protested at the loss of their right to graze their livestock and gather firewood without success. After the enclosure bill was enacted in 1801, Brickwood owned a great deal more land on both Croydon and Norwood Commons.

Detail of a map showing how Croydon Common land was enclosed, 1801 (Corbet Anderson 1889). The former Croydon Common is show with a white background in the centre top of the image. Before the enclosure, John Brickwood’s estate already included plots 1451-1463 from Coney Lane (now Cherry Orchard Road) to the west up to the boundary of Great Mead (now Tunstall Road) to the east. After the enclosure, he also owned the plots numbered 653, 691, 692, 693, 694, 696, 697, 699, 675, 677 and 679, as well as other land in the parish of Croydon.

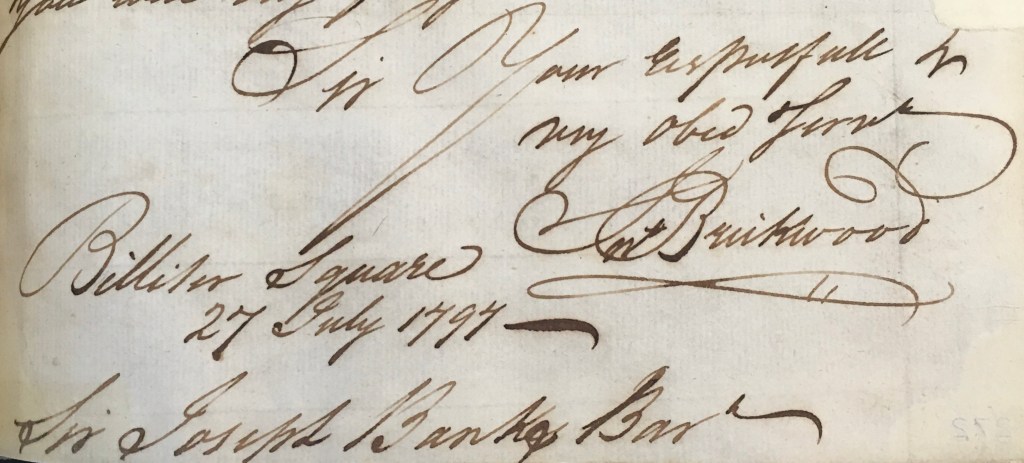

Sir Joseph Banks sent a letter to Brickwood’s Croydon home in 1797, though he responded from his London home in Billiter Square. Banks was the adviser to George III on the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew. He wrote to John Brickwood asking him for contacts in Canada that might help his agent gather specimens in that land for “the Garden”. Brickwood advised Banks of the quickest route to Niagara and promised to send letters to his friends there who could help the agent both on his journey and in forwarding his collections to England. In a subsequent letter, Brickwood sent the letters of recommendation direct to Joseph Banks, enclosing a small parcel which he asks to be taken to his friend Mr Hamilton in Niagara. He states that his friend will be able to help the agent (Mr Mapson) in any part of Canada. Brickwood is probably referring to Robert Hamilton the founder of Queenston in Upper Canada (whose second wife was a native American woman called Monette. Originally his slave, he freed her after she had given birth to their third child).

John Brickwood’s signature on his letter to Sir Joseph Banks, 27 July 1797 (Documents reproduced with the kind permission of the Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew Banks Letters Vol 2 JBK/1/6 ff169)

Two years later, John Brickwood is noted as the captain in command of 40 men in the Croydon Volunteer Cavalry. The occasion was a parade on Wimbledon Common on 4 July 1799 when King George III reviewed the Surrey Yeomanry and Volunteers. 60 Croydon infantry men, under Robert Harris, manoeuvred and fired three volleys, then Brickwood’s cavalry troop went through their sword exercises. Yeomanry and Cavalry units had been formed in many counties for local defence to defend the country against an invasion by Napoleon or subdue any civil disorder within the country. Four troops of Surrey Yeomanry had been raised in 1794, then formed into a regiment in 1797 under the command of Lord Leslie (later the 13th Earl of Rothes). Brickwood continued in post until at least 1806, but as the threat of invasion passed, the Croydon Volunteer Cavalry dwindled away until 1812 when the returns reported “no effective men”.

Model of Lord Leslie in the uniform of the Surrey Yeomanry Cavalry 1806 (from https://suburbanmilitarism.wordpress.com/2020/04/24/a-portrait-of-the-surrey-yeomanry-cavalry/). John Brickwood would have worn a similar uniform when he was captain of the Croydon Volunteer Cavalry. It included a black fur head dress with a scarlet plume, a light blue jacket with red collar and cuff, light blue pantaloons, crimson sash, silver braids, buttons & chains and black boots and buff gloves.

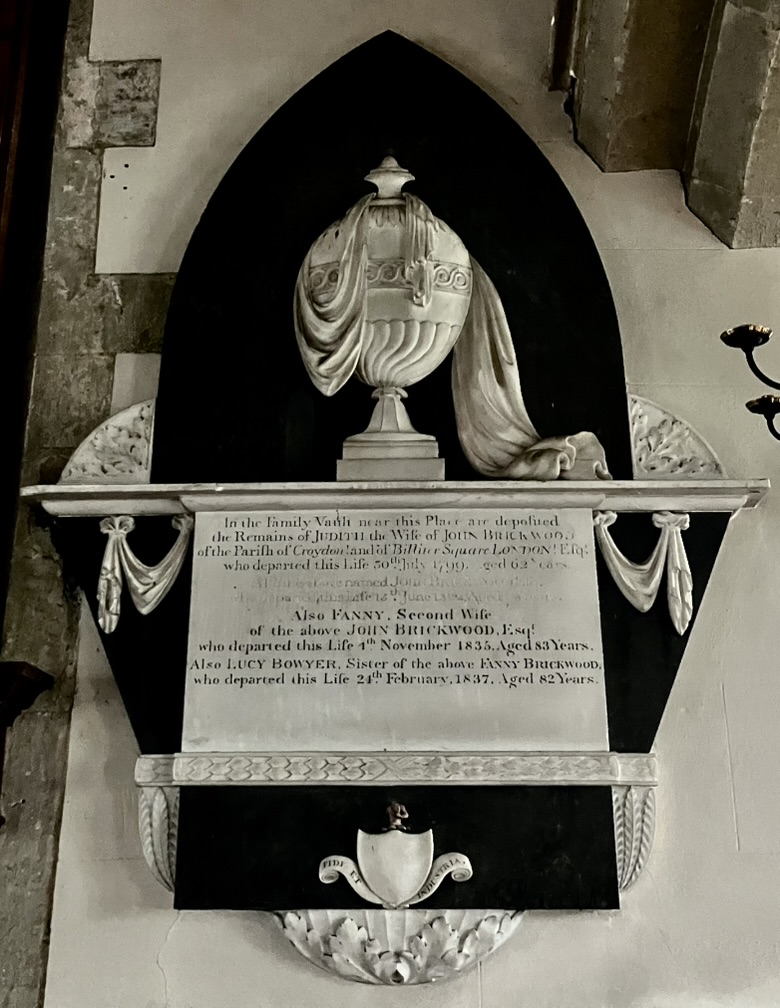

Less than a month after the parade on Wimbledon Common, Judith Brickwood died and was buried in a tomb erected in the middle chancel of St John’s, the parish church of Croydon. Just over a year later, on 6 November 1800, John Brickwood married Fanny Bowyer at All Saints Church in Hertford. In 1802, he was granted leave from Lambeth Palace to move the corpse of his first wife to new tomb in All Saints Church, Sanderstead.

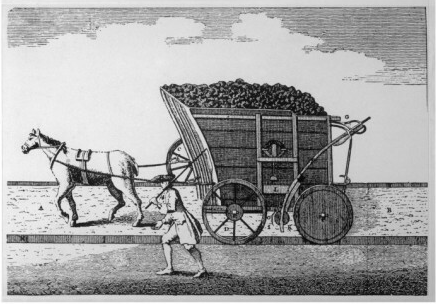

Horse pulling a load on the Surrey Iron Railway (https://www.londonremembers.com/subjects/surrey-iron-railway-company?memorial_id=3492)

John Brickwood was one of the proprietors of the Surrey Iron Railway named in its Act of Incorporation 1801. This railway ran from Pitlake in Croydon to the Thames at Wandsworth, using horses, mules & donkeys to pull goods wagons along its rails. The railway did not flourish, partly because the Croydon Canal provided an alternative route to the Thames (part of its route is commemorate in the roads Canal Walk and Tow Path Way, off Davidson Road). Dividends paid to shareholders were low and ceased entirely after 1825.

A plaque commemorating the Surrey Iron Railway can be seen on the front of the House Reeves, Church Street, Croydon (https://www.londonremembers.com/memorials/surrey-iron-railway-company-croydon)

At the turn of the century Brickwood was also involved in setting up the hemp industry in Canada. Hemp was used to make rope & twine. The cost of importing it into Britain, mostly from St Petersburg, was £1.5 million a year. Robert Hamilton had written to Brickwood in 1801 suggesting that as there was little hemp grown in Canada, a bounty for the greatest amount of hemp grown might encourage its cultivation. As a result, the Society of Arts offered considerable premiums for its cultivation there. In 1804, more than 2500 cwt (127,000 kilos) were exported to London from that province.

On 1 October 1809, John Brickwood (the elder), John Brickwood (the younger, probably John Strettell Brickwood, the son of his youngest brother Lawrence), John Rainier, William Morgan and Joseph Starkey began banking together. They received funds from many people from all over Britain, ranging from £30, 231 4/- deposited by a Glasgow merchant to £1 12/6d from a Hackney bricklayer, to whom they issued promissory notes. On 6 July 1810, the bankers instructed an employee not to make any more payments, to return any cheques or bills presented and to say that they were not at home. The following day, a memorandum declaring them bankrupt was issued at The Baptist Head Coffee House, Aldermanbury. Assignees were appointed to sell the estates & effects of the bankrupts and manage the process of reimbursing the creditors. The London Gazette asked creditors who had proved their debts to meet the assignees at The George & Vulture Tavern in Cornhill on 15 August 1810 to agree further actions.

On 18 August 1810, John Brickwood the elder made a full disclosure of his estate in the London Gazette and his property in Lime Street and Croydon was seized. Despite the fact that payments were still be made to creditor as late as 1864, he was able to buy back Brickwood House and some of its grounds at auction the following year for £7500 (£750,000 today). However, these grounds had now shrunk to the area to the north of Addiscombe Road bounded by today’s Cherry Orchard Road, Cedar Road and Bisenden Road. By now he was in his mid-60s, but he continued with his business interests. He appears to have remained the colonial agent for Bermuda as late as 1813 and he was involved in land transactions in the island of Grenada in 1814.

Brickwood’s estate originally covered the entire area north of Addiscombe Road between what became Cherry Orchard Road and the location of St Mary Magdalene’s Church, as well as many plots of land further north. After 1810, it was reduced to the land bounded by the later Cherry Orchard, Cedar and Bisenden Roads. Addiscombe Lodge was subsequently built on the land sold to the east, with its own semi-circular drive leading from Addiscombe Road (Ordnance Survey 1898).

Life in Croydon sources

- Common Pleas – Recovery Roll – 832/81, transited by C.G. Paget, Notebook 15:273-274 (Croydon Archives)

- Lokke, C.L., 1938. London merchant interest in the St. Domingue plantations of the émigrés. The American Historical Review 43/4, 795-802.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toussaint_Louverture#/media/File:Toussaint_Louverture_-_Girardin.jpg

- Anon. n.d. Notes from a reproduction of a print of “The Seat of John Brickwood” 1805 by John Hassell. Original in the London Metropolitan Archives SC/GL/PR/VI

- Garrow, Rev. D.W., 1818. The History and Antiquities of Croydon. London: W.Annan Pp.39

- Corbett Anderson, J., 1889. Croydon Enclosure 1787-1801. Croydon. Pp.76-9, 108-109.

- Kew Garden Archives Banks Letters Vol 2 JBK/1/6 ff169

- Kew Garden Archives Banks Letters Vol 2 JBK/1/6 ff171-172

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monette_(slave) retrieved August 2023

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Hamilton_(judge) retrieved August 2023

- https://web.archive.org/web/20070708200648/http://www.regiments.org/regiments/uk/volmil-england/vcav/surrey.htm retrieved August 2023

- Harrison-Ainsworth, E. D., 1928. The history and war records of the Surrey Yeomanry (Queen Mary’s Regt.). 1797-1928. London: Printed for the Regimental Committee by Messrs. C. & E. Layton. Pp 22.

- Butt, C.R., 1962. Volunteer force in Surrey, 1799-1813. Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research 40, 207-213.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20070708200648/http://www.regiments.org/regiments/uk/volmil-england/vcav/surrey.htm retrieved August 2023

- Buckell, L.E., 1950. The Surrey Yeomanry Cavalry. Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research 28/116: 171-172.

- https://suburbanmilitarism.wordpress.com/2020/04/24/a-portrait-of-the-surrey-yeomanry-cavalry/ retrieved 14 Sept 2023

- Lambeth Palace Library VH 79/120

- Mcgow, P., 2001. Notes On The Surrey Iron Railway. The Wandle Industrial Museum https://wandle.org/surreyironrailway/header.html accessed August 2023)

- Anon. 1803. Papers in Colonies and Trade, Transactions of the Society, Instituted at London, for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce, 21: 442 – 454.

- Anon. 1804. Papers in Colonies and Trade, Transactions of the Society, Instituted at London, for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce, 22: 345-346.

- Public Records Office B 3/252, B 3/253, B 3/254

- Public Records Office CO/37/71

- http://agenealogyhunt.blogspot.com/2010/09/part-372s-smith-robertson-genealogy.html access accessed August 2023

- Ordnance Survey 1898 Reproduction of Sheet 14.10, Central Croydon 1895 (2nd edition 1898). Gateshead: Alan Godfrey Maps

- Croydon Archives C.G.Paget Notebook 15:273-4

- Croydon Archives C. G. Paget Notebook 3 List of Copyholders: 33

- Croydon Archives fS70(336) Croydon Land Tax Assessment 1790

Death and legacy

All Saints Church, Sanderstead

When John Brickwood died on 15 June 1822, aged 78, the auctioneer John Blake noted that “He was universally esteemed and deeply regretted by all.” He was interred in the crypt at All Saints Sanderstead, where his first wife already lay. In his will, he directed that Brickwood House was to be sold by his executors and the amount raised from the sale (once debts, funeral & legal expenses were deducted), should be invested with the dividend paid to his second wife, Fanny, during her lifetime. However, he also directed a large number of bequests to be paid out of the money before it was invested to family members, his executors, friends, clerks and servants, at least £7350 in total (£1.152 million today). He left his shares in the Pelican Life Assurance Company and nearly all his personal belonging to his “dear wife ffannny”, except the billiard table (to be sold with the house) and those items bequeathed to others.

One friend, John Grantham was to receive a “portrait of Brickwood on his horse, pair of pistols, volunteer sabre, plan of Croydon Common & Norwood Common made by Mr Bainbridge, the Surveyor appointed under the Croydon Inclosure Act”. This is likely to be John Grantham (1775–1833), a civil engineer who was living in Croydon in the early 19th century. In 1811 he had assisted Dudley Clark, resident engineer of the Croydon Canal, to make a plan of its route. 1817 – 1818 he built Croham Hurst House, now a listed building. However, he is best known as the surveyor of the Shannon Navigation inland waterway.

On 20 July 1823, the executors of the will raised a complaint at the Chancery Court. They believed the value of Brickwood’s estate to be insufficient for the payment of his debts and his legacies in full. They propose that all those due to receive substantial legacies should have them “abated”. Fanny Brickwood did not agree that this should apply to her share of the estate, just those of the others. These included Mary Blake, a sister-in-law of John Brickwood, and the surviving children of his brother Lawrence (himself by now also deceased). Needless to say, they did not agree.

Fanny herself died in 4 November 1835, aged 83, in Cadogan Place, London. She joined John in the vault at All Saints Sanderstead, together with his first wife Judith. Two years later, Fanny’s spinster sister, Lucy Bowyer of Clapham, was interred with them.

It was John Blake, the auctioneer who lived at 65 Park Lane, who bought the house in 1822. Blake did not occupy Brickwood House himself, letting it to a series of tenants. These included, from 1823-28, Sir Benjamin Hallowell, a Commander in the Royal Navy who had served with Nelson.

Brickwood House 1908 (Gent 2002:90).

The house and grounds were put up for sale in August 1907. In the sales particulars, the house is described as three floors high (plus a basement) and to include a billiards room. It was fitted with electric light throughout. The grounds covered 16 acres which included stabling for five horses and a coach house for four carriages, plus two tennis courts, two walled kitchen gardens, vineries and a cowshed. It was to be sold free from restrictions to “permit the erection of shops, businesses, factory premises, superior residences or small villas”.

The house was demolished in 1908 and the land divided into the streets we know today and is commemorated by the name of one of them – Brickwood Road. Some of the trees that lined the southern edge of the estate were left in place in the raised bed lining Addiscombe Road. This stretch of road became known as The Boulevard as a result.

Early 20th century postcard of The Boulevard, facing towards the west.

Death & legacy sources

- Croydon Archives AR168 Diary/Commonplace Book of John Blake

- Public Record Office MS 11/1659/126 https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/D153945retrieved August 2023

- Cox, R.H. and Gould, M.H., 1998. Civil engineering heritage: Ireland. London: Thomas Telford Publications:. Pp. 210, 248.

- Skempton, A.W. (ed.), 2002. Biographical dictionary of civil engineers in Great Britain and Ireland. Vol.1 1500–1830. Berlin: Wiley-VCH Verlag. Pp.26

- https://www.dib.ie/biography/grantham-john-a3577 retrieved August 2023

- Croham Hurst House https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1358820 retrieved August 2023

- Public Records Office MS C 13/2174 10 & 34

- Anon. n.d. Notes from a reproduction of a print of Brickwood House 1805 by John Hassell. Original in the London Metropolitan Archives SC/GL/PR/VI

- Croydon Archives S70 (92) BLA “Attribute to the memory of the late John Blake” from the Surrey Standard, 28 February 1852

- Croydon Archives Sales Particulars of Brickwood House

- Gent, J. 2002. Croydon Past. 2002. Philimore & Co Ltd: Chichester

- Ward, J., 1883. Croydon in the Past Pp.20