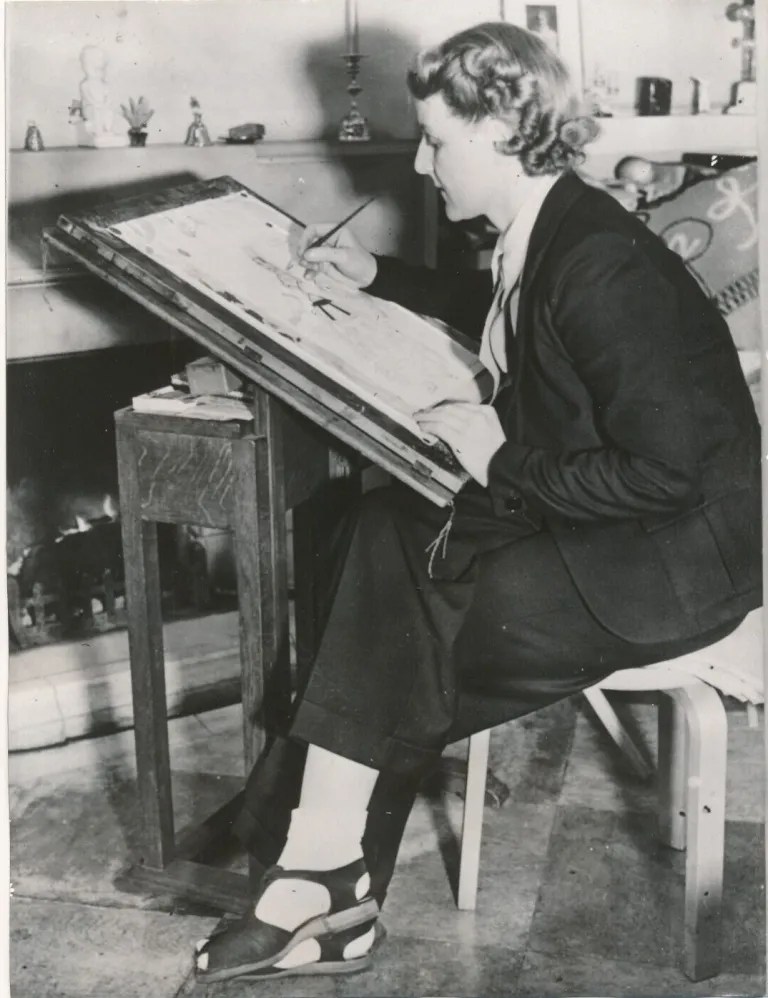

Elizabeth Haffenden at work in the 1940s, during wartime austerity

Norwood to Hollywood: Oscar-winner who dressed the stars

Witten by David Morgan

Posted on June 9, 2024 by insidecroydon

The next time the sword and sandal epic Ben-Hur is repeated on television, don’t switch off just because you’ve already seen it umpteen times before. Watch it again, in a fresh light, because one of the many awards the 1959 Hollywood movie collected was the Oscar for best costume design, and all those togas and robes from Jerusalem 2,000 years ago came straight out of 20th Century Croydon. That was not the only Oscar won by Elizabeth Haffenden, either, as she enjoyed a stellar career as a costume designer over four decades, with such stars as Elizabeth Taylor and Charlton Heston wearing her creations on set.

Born in Croydon on April 18, 1906, she was a daughter of James Wilson-Haffenden and his wife Edith. The family lived at Homewood, Hazeldean Road, off Addiscombe Grove. Wilson-Haffenden earned his living as a wholesale draper. Elizabeth went to the Croydon School of Art and later attended the Royal College of Art. Before moving into costume design, she worked as a commercial artist.

Material evidence: Haffenden’s search for the right look for movies stretched far and wide

Haffenden’s first job in film was with Sound City, later known as Shepperton Studios, in 1933. The first film she worked on was Colonel Blood, an historical drama set in the 17th Century. She spent several years working as an uncredited design assistant for Rene Hubert on several Alexander Korda films, including in 1940, The Thief of Baghdad. During this time, she also did some work in the theatre. Her costume designs were seen in the 1938 production of The Sun Never Sets at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. In the early 1940s she joined Gainsborough Studios, based in Hoxton, who were famous for their period melodramas – lots of big frocks and big hair… Haffenden was soon promoted to become the director of the costume department. The constraints of material production and availability during wartime rationing brought their own challenges, but nonetheless, Haffenden was credited with making sumptuous costumes.

The right look: Heffenden’s original Ben-Hur costume sketch for Esther, played by Haya Harareet. Note Heffenden’s signature, on a sketch drawn in 1957

One writer described her designs as making women’s bodies appear “opulent and mysterious, both by the choice of cut and fabric and by the decoration”. In her work at the Gainsborough Studios, Haffenden developed a system which she called “a costume narrative”, where clothing could tell its own story. For example, a couple falling in love would have similar detailing on the costumes, or might wear similar colours. Four key people at Gainsborough were responsible for their successes. Along with Haffenden, writer-director Leslie Arliss, cinematographer Arthur Crabtree and production designer John Bryon devised a visual approach which made the films distinctive and belied their modest budget.

The 1944 production of Love Story was one of the films for which Haffenden created outfits that reduced ration coupon expenditure in one area so that she could apply for points to purchase material for more extravagant ones. Margaret Lockwood, the star of the film, was given to wear a skirt, a blouse and jacket in the same material and several blouses each made from a recognisably different cloth. These could be worn in various combinations, with different accessories, to make it look like Lockwood was wearing multiple outfits.

The 1945 film, The Wicked Lady, about a noblewoman (Lockwood, starring alongside James Mason) who took to highway robbery, caused quite a stir with Haffenden’s bold designs. The low cut dresses worn by Lockwood raised a few eyebrows and gave the censor “cause for concern”. Before the film was released in America, some of the scenes had to be reshot, so that Lockwood revealed less cleavage. It was a huge box-office success in this country.

Opulence: Robert Shaw, as Henry VIII, and Paul Scofield, as Thomas More, in A Man For All Seasons, for which Heffenden won her second Academy Award

One of the design assistants who worked under Haffenden after she was demobbed in 1945 was Julie Harris. Harris went on to work on the James Bond films, Casino Royale in 1967 and Live and Let Die in 1973, and always credited Haffenden with teaching her the basics of her trade.

Haffenden left Gainsborough in the 1950s to join MGM British Studios at Elstree. From the late 1950s, she worked freelance. Ben-Hur is one of the most successful of all 20th Century movies. It had the largest budget $15.2million, as well as the largest sets built, of any film produced at the time. No ration-book scrimping here. Haffenden worked for a whole year in preparation of the costumes before any filming began. She was in charge of a department of more 100 who made thousands of outfits – this was an epic movie behind the scenes as well as on the screen. Silk was brought in from Thailand, woolens were made in Britain, shoes in Italy, lace from France and costume jewellery was purchased in Switzerland. It was a far cry from her days of creating costumes on a tight budget at Gainsborough. Her impressive creations won the Oscar for Best Costume Design. Her star was shining brightly across the world of cinema. Haffenden worked closely with her friend Joan Bridges on Ben-Hur. The two had met when they were both working at Gainsborough Studios and they collaborated successfully on 16 films.

The colours chosen for costumes worn by Maggie Smith in the 1969 film The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie were of particular significance. Muriel Spark gave little indication of costume in her novel but Haffenden and Bridges’ visually striking designs brought out Brodie’s flamboyance. Colour was a way in which they could show Brodie’s unconventionality, in this instance, red. When being dismissed by the headteacher from her school, Brodie wore a more sombre suit of purple. Haffenden and Bridges’ knowledge and awareness of colours, textures and fabrics kept them in great demand by filmmakers.

Haffenden was in great demand for her work, and she was hired to work alongside some of the great directors, dressing some of the greatest actors on some of the greatest films. From Moby Dick, starring Gregory Peck and directed by John Huston, to The Sundowners, starring Deborah Kerr, Robert Mitchum and Peter Ustinov filmed in the Australian outback by Fred Zinnemann, to the flamboyance of Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (based on an Ian Flemming story, with Roald Dahl’s screenplay), to musical Fiddler on the Roof, to the more contemporary dress for the Frederick Forsythe thriller The Day of the Jackal, also directed by Zinnemann, Haffenden and Bridges contributed hugely to the world of cinema.

Haffenden’s second costume design Oscar came in 1966 with another Zinneman film, A Man For All Seasons, set in the turbulent Tudor court of Henry VIII (played by Robert Shaw, long before he had to get a bigger boat…), with playwright Robert Bolt’s screenplay written around the crisis of conscience for Thomas More, played by Paul Scofield. The film won six Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor (for Scofield), and with Haffenden and Bridges jointly named as winners for Best Costume. A Man For All Seasons won seven BAFTAs, with Haffenden and Bridges again jointly named for their costume design.

Haffenden had begun work on a new project when she died in Hampstead in 1976. Bridges continued designing for the film, Julia, starring Jane Fonda and Vanessa Redgrave, which was released the following year. Bridges received an Academy nomination for the picture.

Haffenden’s family connections to Croydon are also worth noting. Her surname should really have been Wilson-Haffenden. That was down to a family change.

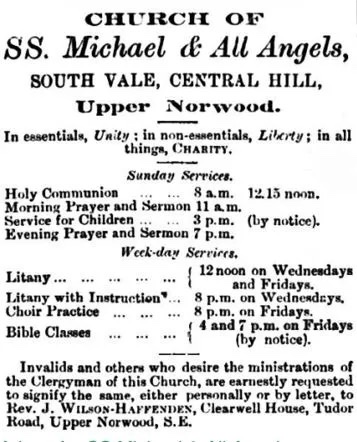

Church for scandal: all was not smooth for Elizabeth Haffenden’s grandfather, Rev John Wilson-Haffenden

Her grandparents had made a successful appeal to the Crown to be able to add the name of Haffenden, her grandmother’s maiden name, to the family name, Wilson. This was so that they could, “testify grateful and affectionate respect of the late Alfred Haffenden”, as Elizabeth’s grandmother had been named a co-heir of his legacy. Alfred Haffenden had lived at Homewood near Tenterden in Kent.

After Alfred Haffenden’s death, Rev John Wilson-Haffenden (as he was then known from 1872 onwards, Elizabeth Haffenden’s grandfather), moved into the house, enjoying the legacy inherited by his wife Charlotte. John gained a highly esteemed and revered position in his local town, becoming a JP as well as being Mayor of Tenterden in 1879 and 1880.

Strangely though, the Wilson-Haffenden’s were nowhere to be found in the 1881 census for Tenterden. Instead, he turned up at Norwood, living in Tudor Road and advertising that he had begun a series of Church of England services at The Assembly Rooms, Westow Street, Upper Norwood. New premises were soon found and SS Michael and All Angels in South Vale, Central Hill, South Norwood, was open by July 1883. But the wardens of the new church had written to the local paper telling them that Wilson-Haffenden was not entitled to hold Church of England services because “he was disqualified to hold preferment in the Established Church of England”. Whatever had he done?

Wilson-Haffenden claimed in his defence that he had taken advantage of the Clerical Disabilities Act of 1870 which allowed a clergyman to enter Parliament. Whether he actually tried to become an MP wasn’t clear. He wanted to make a fresh start in his ministry, but didn’t have the permission of the Archbishop of Canterbury. He accused the churchwardens of being unchristian.

Two further pieces of evidence reveal the extent of Rev Wilson-Haffenden’s troubles. He appeared at a bankruptcy court in 1885, where he explained that he had to sell his estate to pay his debts, following a series of bad harvests. He hadn’t been able to obtain a curacy anywhere, so he built a chapel in Norwood, an iron church. He got into more financial difficulties, as he didn’t have the money to complete the project and the new church was forfeited to the ground landlord.

His wife’s name never appeared in any church literature in Norwood. It seems likely that Charlotte lived apart from him. It was reported in the Morning Post in November 1878 that she was a resident at the Alexandra Hotel, Hyde Park Corner, with a daughter.

Wilson-Haffenden didn’t learn lessons from his bankruptcy, however. A church, Emmanuel, in Small Heath, Birmingham, was erected, paid for entirely on credit, in 1895. But Wilson-Haffenden couldn’t get enough money to keep the church going and it was quickly closed down with an auction to raise money to pay off the debts. This was to be his last venture, as he died later that year. Charlotte emigrated to Queensland, where she remarried.

The bankrupt vicar’s granddaughter lived a much more storied life, her journey from a house in Hazeldean Road, Croydon, to the Academy Awards ceremonies in Los Angeles alongside the biggest Hollywood stars of the day must have been quite the experience.

Perhaps Elizabeth Haffenden is worthy of a brief season of the films she helped to make at the David Lean Cinema, just a short walk from where she grew up?