When the British Parliament approved the Act emancipating enslaved people in 1833, their owners were entitled to compensation for the loss of their human property. The compensation package was worth £20 million, the equivalent of 40% of government expenditure at that time. The database of British Slave-Ownership takes the records of those compensated as a starting point.

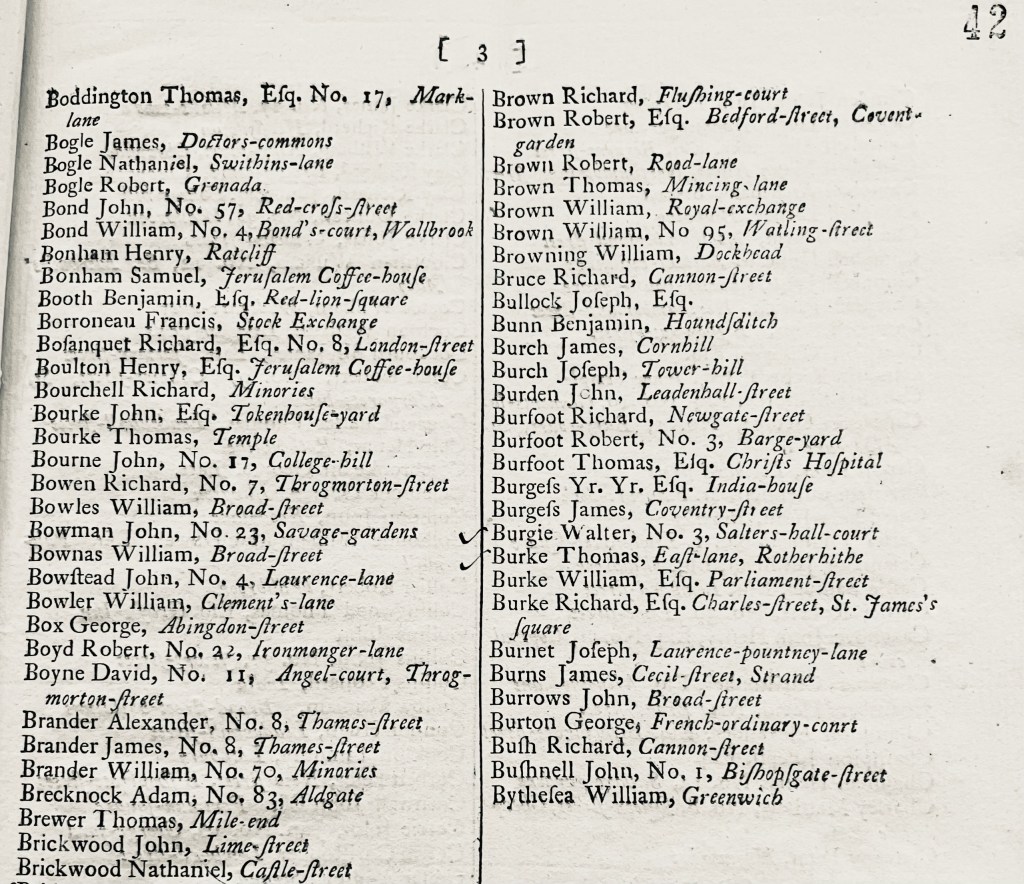

No one living in what is now the ECCO area appears on this list. This may not be surprising since there were relatively few houses in the area at that time. Apart from a cluster of small dwellings at the junction of Cross Road and Cherry Orchard Road, it was largely divided between the Leslie Lodge estate (along Lower Addiscombe Road) and the Brickwood estate (along Addiscombe Road). The latter had originally stretched from Cherry Orchard Road to Tunstall Road. It was created by John Brickwood, a merchant and banker, at the end of the 18th century. John died in 1822, so even if he had owned slaves, he would not have appeared on the list of those compensated. However, he had had a long history of involvement with the Caribbean.

In 1784, John Brickwood was appointed a colonial agent for the Bermudas. Colonial agents were based in London. They were paid by colonial governments to represent them to the British government, securing acceptance of controversial colonial legislation and heading off British policies objectionable to the colonies. Bermuda was one of the first colonies to use enslaved people. As colonial agent, John Brickwood represented the needs of their masters.

His main role appears to have been to pass on correspondence from the government of Bermuda to the relevant officials in the British government and chase them for action. These included such people such William Wyndham Grenville, the Home Secretary. Much of the correspondence was to do with the government of the Bahamas interfering with the gathering of salt by people from Bermuda from ponds on the Turks islands. Of course, it would not have been the British settlers that would gathered the salt, but the enslaved people they owned. An account of how they suffered when doing so can be read in The History of Mary Prince, a West Indian Slave, the first autobiography of an enslaved African women to be published (in 1831).

“I was given a half barrel and a shovel, and had to stand up to my knees in the water, from four o’clock in the morning till nine, when we were given some Indian corn boiled in water, which we were obliged to swallow as fast as we could for fear the rain should come on and melt the salt. We were then called again to our tasks, and worked through the heat of the day; the sun flaming upon our heads like fire, and raising salt blisters in those parts which were not completely covered. Our feet and legs, from standing in the salt water for so many hours, soon became full of dreadful boils, which eat down in some cases to the very bone, afflicting the sufferers with great torment. We came home at twelve; ate our corn soup, called blawly, as fast as we could, and went back to our employment till dark at night. We then shovelled up the salt in large heaps, and went down to the sea, where we washed the pickle from our limbs, and cleaned the barrows and shovels from the salt. When we returned to the house, our master gave us each our allowance of raw Indian corn, which we pounded in a mortar and boiled in water for our suppers.”

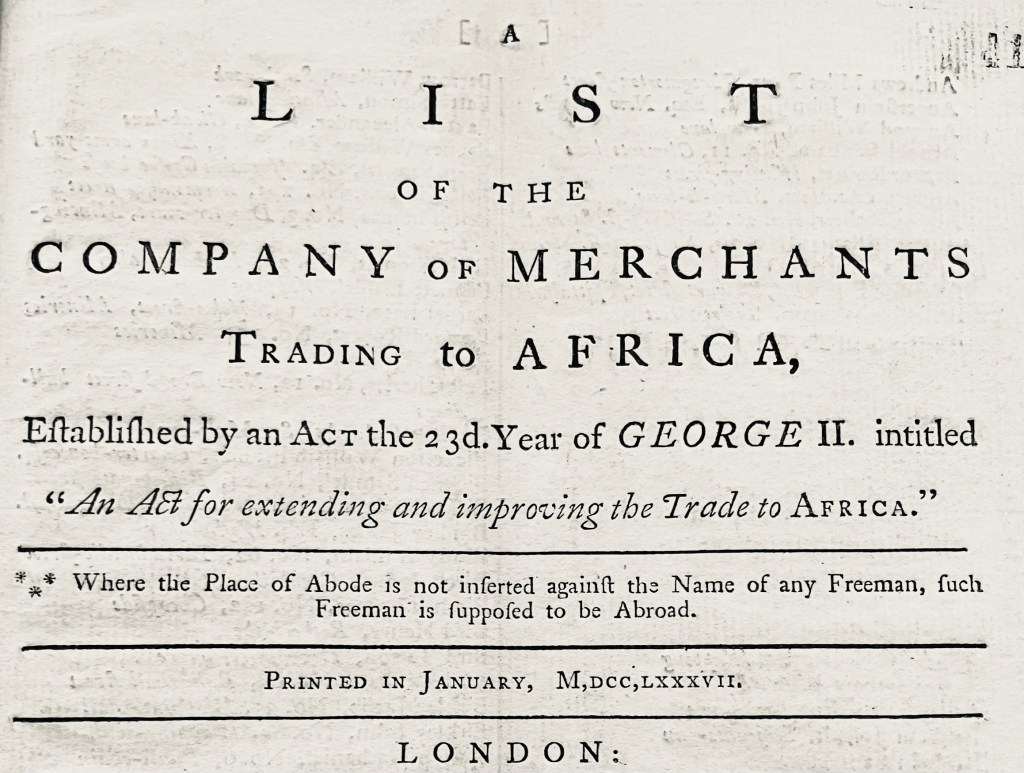

In 1787, John Brickwood and his brother Nathanial are listed as London members of Company of Merchants Trading to Africa. Membership of the Company was open to anyone who paid 40/-. This company was not allowed to trade in enslaved people itself, but staffed and maintained the forts on the Gold Coast and the Gambia that helped English traders to do so. Brickwood and his brother may have provided supplies to the forts (food, ammunition, building materials, medicines) and goods to be traded to the African people living around the forts (to pay for labour, fresh food & building) or to be given to those of importance to maintain good relations. The items most largely in demand by the Africans were rum, brandy, woolen & cotton materials, firearms and gunpowder. The ships that carried these goods also carried new recruits to work in the forts and orders for the governor. John Stables of Park Hill also appears on the list (as he did in 1778).

From 1792-93m Brickwood was paid by the British government to shipping goods to the Bermudas for the army. By then, he was already a partner in the firm of Brickwood, Pattie & Co. They lent money to French plantation owners living in London, fugitives from the French revolution. The loans were secured on the title deeds of their plantations. The émigrés were expecting large annual profits from their estates, based on the labour of their enslaved people, to pay back the merchants. In 1793, owners of plantations in the colony of St Domingue (Haiti) persuaded the British government to send troops to conquer the French colony. However, the French government freed all their slaves in 1794 and these plantations could no longer turn a profit. Both the émigrés and the British merchants pressed the British government to continue in their campaign, in the hope of reinstating slavery (still legal in the British empire) and thus making good their losses. However, in 1798, the British troops withdrew completely from the island. The title deeds were no longer valid and firms, such as Brickwood, Pattie & Co, made substantial losses.

Some compensated slave owners invested substantial funds in railway companies involved in the development of the London and Brighton Railway, which opened in 1841. Others had local connections, such as

- William Bond, who died at Park Hill in 1794 and had owned the plantations of Mona, Cardiff, Spring and Surrey on Jamaica (which had 817 enslaved people at the time of emancipation).

- John Swindell, who died in Lansdowne Road in 1863 and had owned the Hope & Colquhouns and Mansion estates on St Kitts (which had 308 enslaved people at the time of emancipation).

- John Lunan of St Catherine, Jamaica, who left £10,000 to his two daughters. One of them, Maria Barry, died in Dingwall Road in 1882.

- Thomas Gillespy, who died in Sydenham Road in 1872, having inherited the compensation for 109 enslaved peoples on the Claremont estate in Jamaica.

- Reverend Robert Hackshaw, who lived in Lansdowne Road in 1871 and had inherited the compensation from 213 enslaved people on the Three Rivers estate on St Vincent.

However, just as some local people benefited directly from the exploitation of enslaved people, others campaigned against it. After emancipation had been achieved in the British Empire, they turned their attention to campaigning to end slavery elsewhere in the world and supporting freed slaves. John Morland was a prominent campaigner. An elder in the Society of Friends, he had moved to Croydon in 1844. He hosted former enslaved people, such as William Wells Brown and Samuel Ringgold Roper, at his home in Heath Lodge, when they came to speak in Croydon. Wells Brown reported that “It was my first welcome in England. The assembly was an enthusiastic one (and)… I left Croydon with a good impression of the English, and Heath Lodge with a feeling that its occupant was one of the most benevolent of men”. After Morland died in 1867, the road that ran outside Heath Lodge was named after him..

Another former slave who spoke locally, was Reverend Thomas Lewis Johnson. He ran children’s services at the Croydon Skating Rink, on Cherry Orchard Road, in the early 20th century. You can read his incredible life story, which involved missionary work both in Britain and Africa, in his auto biography “Twenty-Eight Years a Slave, or the Story of My Life in Three Continents”.

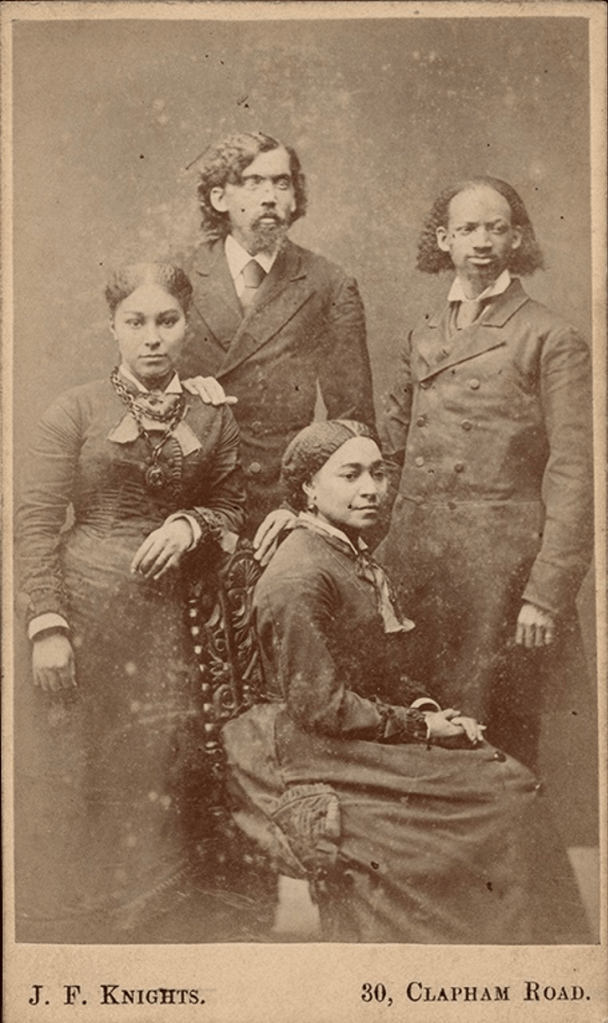

Image from the Autograph ABP website

Thomas Johnson (on the right) with his wife (seated) had both been enslaved. They came to London from America in 1876 as beneficiaries of the Manchester YMCA and the Baptist Missionary Society of London. The other couple are C.H. Ricardson and his wife who arrived a year later to accompany the Johnson’s on their mission. The photograph was taken in 1878, shortly before they left for West Africa. Johnson taught and preached in the village of Bakundu in Cameroon. However, after his wife died, his own ill health forced him to return to England in 1880. He continued to preach and give lectures on Africa in Ireland and America, as well as England. He published his autobiography in 1882 and became a British subject in 1900.

Sources

- Anon. (n.d.). Notes from the reproduction of a print of Brickwood House 1805 by John Hassell.

- Anon. (1844). Croydon Tithe Award Index. Croydon Museum & Archive Service.

- Corbett Anderson, J. (1889). Croydon Enclosure 1787-1801. Croydon.

- Creighton, S. (2017). Croydon’s connections with the British slavery business, Proceedings of the Croydon Natural History and Scientific Society 20 (1): 12-45.

- Creighton, S. (2019). Croydon’s Black African & Caribbean History before The Windrush. History & Social Action Publications: London.

- Gent, J. (2002). Croydon Past. 2002. Philimore & Co Ltd: Chichester

- Lokke, C.L. (1938). London merchant interest in the St. Domingue plantations of the émigrés, The American Historical Review 43 (4):795-802.

- Martin, E. C., January 1922. The English establishments on the Gold Coast in the second half of the eighteenth century. Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 121:167-208

- Penson, L (1924). Colonial Agents of the British West Indies. University of London Press: London.

- The History of Mary Prince, a West Indian Slave. (1831). https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/prince/prince.html

- Public Record Office T70/1508

- The African Company of Merchants https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/African_Company_of_Merchants