The 550-year rise and fall of Croydon’s annual Walnut Fair

Written by David Morgan

Posted on February 25, 2024 by insidecroydon

Thousand of stalls, thousands of visitors – people travelled from London, Surrey and far and wide for Croydon’s annual Walnut Fair

“Try your hand at the Lucky Bag!”

“Walk up! Walk up! The show’s about to start.”

“Walnuts! Crack ‘em and try ‘em before you buy ‘em! Walnuts! Waaal-nuts!”

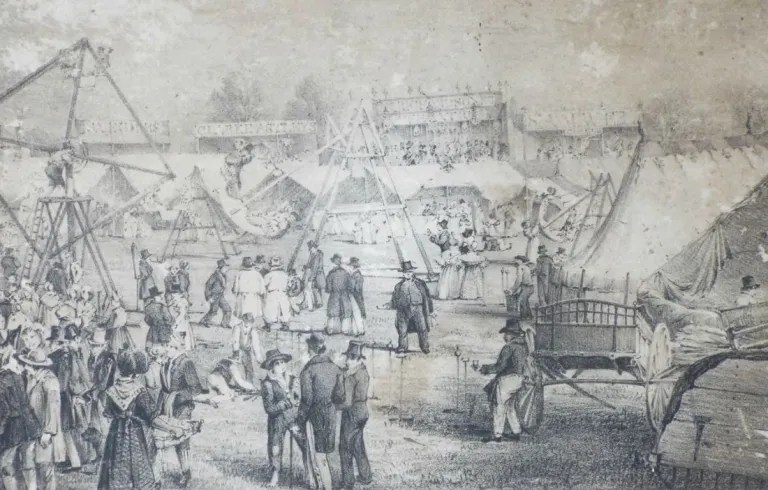

Thousands of visitors would gather at Croydon’s Fair Field in the first week of October 170 years ago or so, in the time of Charles Dickens, and would have heard the cries of the traders and stall-holders at the annual Walnut Fair, held on the Fair Field, which extended along the current George Street, as far as Park Street.

Edgar Browne, the son of Hablot “Phiz” Browne, one of Dickens’ illustrators,remembered being taken to the Walnut Fair as a child back in the 1850s. It was one of the highlights of his year. People came from all over Surrey and London to enjoy the spectacle which had gone on for hundreds of years.

‘The shew of walnuts this year at Croydon was bad’: a newspaper report from 1816, when ‘unfavourable’ weather proved bad for trade

One of the three major fairs in Croydon, it was originally chartered in 1314 by Archbishop Reynolds around St Matthew’s Day, on September 21. The date was changed to October when the new Gregorian calendar was introduced in 1752. Originally held in the area of Surrey Street and Middle Row, and attracting pilgrims travelling to Canterbury, it was moved to Fair Field because of increasing congestion.

There was a newspaper report back in 1730 about the Walnut Fair. It told of a native American king and his princes who were driven from London to Croydon in a coach and four. This royal party were from the Cherokee tribe who sailed to England to sign a trade agreement between the King, George II, and their nation. The report continued, “They were elegantly entertained to dinner at the George and afterwards treated with Sack and Walnuts which is the custom of the fair. It is remarkable that there was the greatest concourse of people on that occasion that has been known for years; and the king was pleased to express that he had not been better diverted since his arrival in England.”

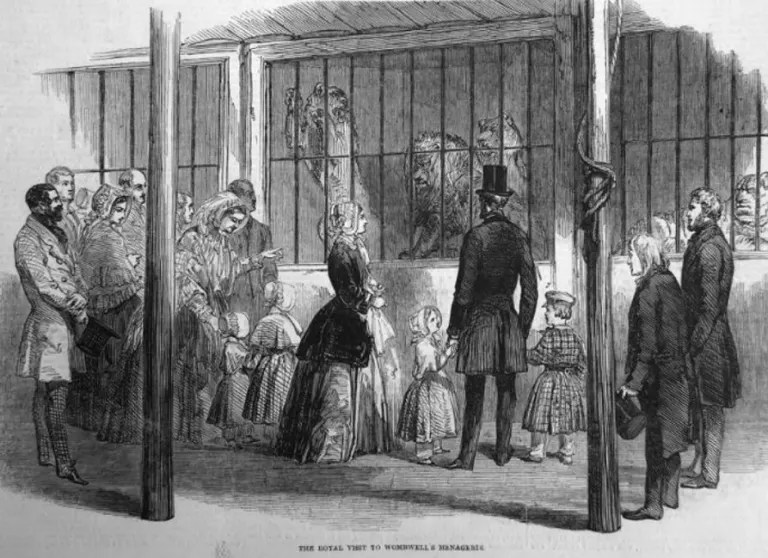

Young Edgar Browne, visiting the fair more than 100 years later, remembered two special highlights. He loved Wombwell’s menagerie and Mrs Jarley’s waxworks.

Royal attraction: Wombwell’s Menagerie was famous enough to see Queen Victoria and Prince Albert bring their children to visit

Wombwell’s exhibits might not be to the tastes of a 21st Century audience but to a young boy in the middle of the 19th Century the opportunity to see wild animals from around the world was too good to miss. There was an interesting story about Wombwell’s visit to Croydon in 1842. On each day of the fair, the elephant in the show was taken into Croydon and was bought a bun at the local bakery. The elephant so enjoyed its treats that in the early hours of one morning, the animal pushed its way out of its cage and made its own way into town. It located the shop, smashed the windows and helped itself to what was found on display. Wombwell described him as “his wonderful and stupendous hanimal, his heliphant”.

‘Wonderful heliphant’: commemorative porcelain shows Wombwell’s ‘immense’ menagerie

At the menagerie, there were bandsmen in Beefeater coats and tigerskin hats blowing bugles to welcome the punters. Huge and colourful animal paintings were hung at the entrance. One newspaper report talked of onlookers being enthralled by a snake charmer with a boa constrictor around his waist. Edgar Browne wrote how he loved to see the feeding time for the animals as well as the performances of the big cats. He remembered that on one occasion the lion tamer was a woman. This was probably Ellen Chapman, nicknamed “the British Lion Queen”, who once performed in front of Queen Victoria. However, even Edgar noticed that the cages seemed rather too small for the animals.

Once out of the menagerie, Edgar Browne went off to the waxworks. There were the usual models of celebrities from around the world but, for a small extra fee, spectators could go into another tent called the Chamber of Horrors where there were tableaux of popular murders. All the people represented in them, according to Edgar, seemed to have fresh complexions and neat hair “as if homicide were a healthy and refining occupation.”

Mrs Jarley was another link with Charles Dickens. The story of her waxworks played a part in the 1841 novel The Old Curiosity Shop.

Browne enjoyed being part of the throng who visited the fair. He wrote that if he went in the afternoon, he and his siblings were taken by the family’s housemaid. When he was older and allowed to go in the evenings, they were accompanied by the groom. The young Brownes were always disappointed when it was time to leave the fair. There was so much to see and never enough time to visit everything.

‘Always on view’: after the Walnut Fair ended in 1868, Wombwells found a permanent home at the new Crystal Palace

Theatre and dance fans were catered for, too. Algar’s illuminated dancing booth was frequented by the officers of the Military Barracks in Mitcham Road and the students of the Military College in Addiscombe. Ladies were seen wearing their elegant evening dresses. Edgar Browne never included in his recollections the two Methodist ministers who stood outside the fair distributing leaflets. Entitled Eight reasons for not going to Fairs, Races and Plays, the parsons came in for much ribbing and leg-pulling from many fairgoers.

According to reports, there were often up to a thousand stalls to enjoy. Coconut shies, with three throws for a penny, and Aunt Sallys, where you had to throw a stick at a model head in order to break the clay pipe in its mouth, were great attractions for youngsters and adults alike. There were even learned pigs! These porkers responded to questions being shouted by their owner by picking up particular cards in their mouths. Dickens wrote about learned pigs in his Mudfog Papers.

Of course, walnuts were for sale in their thousands in sacks, baskets and boxes. The walnuts were originally sourced from orchards in Carshalton and Beddington, but later they were imported from Europe. There were other gourmet treats, too. An 1804 newspaper said: “Geese and ducks boiled until they were tender, roasted ‘til they were brown and served up with a profusion of boiled onions and sage to moisten them.” A visitor to the fair in 1832 wrote: “Even at an early hour my nose was assailed by the fragrant aromas of roasted pork and goose.” The glowing charcoal fires in vast grates of immense width which were situated behind the booths were a real feature of the fair. As well as the number of food stalls at the fair, the local inns and public houses geared themselves up for the huge influx of visitors. An 1832 menu from the Greyhound read:

Goose and sauce 12/-

Fore loin of pork and sauce 12/-

Hind loin of pork and sauce 7/-

Bottle of wine 6/-

Heavy beer 1/- per pot

One report stated that the Greyhound cooked 100 geese for each day of the fair that year. Even if the locals didn’t go the fair, it was the tradition for families to cook their own meal of goose or pork at home. For those folk who possessed a sweeter tooth, the gingerbread stall run by the Boniface family from Reigate was always popular. In case people needed a quick snack as opposed to the full roast pork or goose meal, then they could wander along the “sausage row” where it was said that “hungry mortals swallowed the savoury delicacies as fast as they could be cooked”.

Borough of culture: attempts to review the Walnut Fair foundered

Rowdy and raucous behaviour, as well as thieving and pick-pocketing, began to taint the atmosphere of the fair. Dr Carpenter, a prominent local physician, was a leading voice in a campaign to close down the fair. Complaints in the local papers began to surface in 1859. The final fair was in 1868. Dr Carpenter’s status as a killjoy resulted in stones being thrown through his window and an effigy of himself being burned on Guy Fawkes Day. A centuries-old tradition had come to an end.

In 1987, there was an attempt to revive the Walnut Fair, with the mayor opening a day-long celebration at the Fairfield Halls. But it wasn’t anywhere near the same. The spirit of the old fair and one of the great Croydon traditions is now the stuff only of dusty old books and Dickensian stories.