Hallowell’s voyage from Boston to Beddington via Brickwood House

The naval career of an American-born admiral who provided the hero of Trafalgar with his coffin, traced all the way to Croydon and then to Carew Manor

By David Morgan

Published on April 14, 2024 by insidecroydon

Admirable admiral: Sir Benjamin Hallowell Carew in later life

What is the most unusual gift that you have ever been given? Admiral Horatio Nelson, the hero of Trafalgar, was presented with an unusual souvenir by a fellow naval officer, Benjamin Hallowell. It was a wooden coffin. Far from being shocked, Lord Nelson treasured the present and kept it in his cabin for years afterwards.

Hallowell served under Nelson and fought alongside him in several of the most significant battles of the Napoleonic wars, rising to become a Royal Navy admiral himself in 1830. Between 1823 and 1830, Hallowell rented a house in Croydon.

John Blake, who had a memorial window in Croydon Minster, was the owner of Brickwood House. This fine property in Addiscombe was purchased by him after the death of the man who built it, John Brickwood. Both Brickwood and Blake are remembered in Croydon today because roads were named after them. Blake never lived in his newly acquired property, renting it out to Hallowell.

Hallowell, though, wasn’t a typical English naval officer of his day. He was an American, born in 1761 in Boston to a family who were supporters of the British in the difficult years before the American War of Independence. Hallowell’s father, also named Benjamin, had also seen service in the Royal Navy, and had become a Commissioner of the Board of Customs in the port of Boston. His mother, Mary Boylston, was a second cousin of John Adams, who would go on to become the second President of America, and so were also related to John Quincy Adams, the sixth President.

Colonial home: the Hallowells’ family home in Boston, as photographed in the 1920s

The Hallowells of Boston lived a comfortable life by the standards of the time, with enough income to be able to employ one of the great American portrait painters of the day, John Singleton Copley, to produce family portraits. Mary Hallowell had a portrait painted in 1767 where she is portrayed holding a rock dove in her left hand. His father had his portrait painted a few years before, in 1764, where he is pictured sitting at his desk holding a customs ledger and a quill pen.

Being a customs officer for the Crown in Boston in the late 1760s and 1770s would prove to be a very dangerous occupation. The family’s support of the Crown brought them into conflict with those who were supporting American independence. In August 1765, their house in Roxbury was ransacked by the same mob who set fire to Governor Hutchinson’s house. The family was forced to flee to Jamaica Plain, another suburb of Boston. In 1768, another mob in Boston became so outraged and aggressive that Hallowell was forced to seek safety on a British ship anchored in the port, HMS Romney.

Copley’s work: Mary Hallowell, as painted by John Singleton Copley in 1767

Passions ran deep even with people on the same side. In 1775, Hallowell Senior was involved in a street brawl in Boston with Vice Admiral Samuel Graves, the British Commander in Chief in North America. This was a dispute about harvesting hay. After blows were given and received by both men, Graves’ sword was snatched by Hallowell who broke it so that he wouldn’t have the chance to draw it. Hallowell was so frustrated with Graves and the troops that he led because he could see how ineffective they were becoming in the increasing tensions that would lead to conflict. In 1776, the Hallowell family was forced to flee America for Nova Scotia. After just a few months they sailed for England.

Young Hallowell was aged 14 or 15 when he arrived in England, and wasted little time before joining the navy. Hallowell enjoyed Navy life and was promoted to lieutenant in 1783 having already been involved in the Battle of Chesapeake Bay in 1781, St Kitts in 1782 and the Battle of Dominica later that same year. Hallowell, by then a Commodore on frigate HMS Minerve, was on board the British flagship HMS Victory with Nelson at the Battle of Cape Saint Vincent in 1797. It was Nelson’s successful manoeuvre in the fog and his return to the British line of ships without being spotted by the Spanish fleet which gave Commander Jervis the intelligence he needed about the strength of the enemy. After the battle, Jervis recommended Hallowell to the Admiralty for a command. He was given HMS Lively, in which Hallowell fought in the Battle of Santa Cruz de Tenerife. That was the battle in which Nelson lost an arm.

By the time of Battle of the Nile in 1798, Hallowell was in command of the 74-gun HMS Swiftsure. The British had hunted down the French fleet all the way from Toulon, via Malta, and tracked them to Egypt. Swiftsure, under Hallowell’s leadership, was at the epicentre of the battle. Finding himself at close quarters with the French flagship L’Orient, and being seriously outgunned, Hallowell chose to go on the attack. A fire on board the L’Orient proved impossible to extinguish because tubs of paint and turpentine had been left on deck. Swiftsure and three other ships concentrated their shot on the burning area. When the French flagship blew up, the battle was, in effect, over. Despite being in such close proximity, Hallowell and his ship survived the blast with only a few casualties.

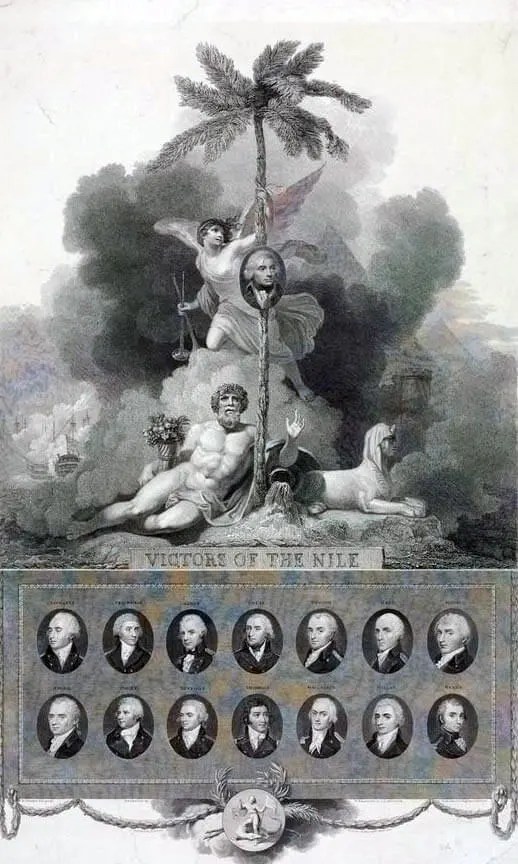

National heroes: Hallowell appeared among the feted naval commanders, with Nelson at the pinnacle, in this 18th Century engraving

Hallowell managed to retrieve the mainmast from the stricken French vessel and ordered his carpenters to work. They produced a wooden coffin which Hallowell sent to Nelson with the following message: “My Lord, herewith a send you a coffin made of a part of the L’Orient’s main mast that when you are tired of this life you may be buried in one of your own trophies, but may that period be far distant is the sincere wish of your obedient and much-obliged servant Ben Hallowell Swiftsure”. On the bottom of the singular present was pasted a certificate, written on paper to the following effect: “I do hereby certify that every part of this coffin is made of the wood and iron of the L’Orient, most of which was picked up by His Majesty’s Ship under my command in the Bay of Aboukir.” Nelson appreciated the gift from one of his “band of brothers”. He kept the coffin, with the lid on, propped up behind the chair in his cabin on his flagship, where he would sit and eat.

Croydon home: Brickwood House, where Hallowell set up home in the 1820s

When he was given his next ship, the Foudroyant, Nelson took the coffin with him, where it remained from many days on the gratings of the quarterdeck. While his officers were looking at it one day, Nelson was said to have come out from his cabin and told them they could look at it all they wanted, but none of them would ever get to use it! And after Nelson was killed at the Battle of Trafalgar in October 1805, when he was given a state funeral through the streets of London to be buried in the vault under the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral, the Viscount was interned in the coffin that Hallowell had presented to him.

Quite how much time Hallowell would have spent in Croydon home as he traversed the world’s oceans isn’t known, but his wife certainly spent much time in Addiscombe. Hallowell was married in February 1800 to Ann, the daughter of Captain John Inglefield. Their eldest son Charles joined the navy and later served a time as his father’s flag lieutenant. Probably, as with many naval officers of the time, the Hallowells chose Croydon because of its location: having a home close to London to attend the Admiralty when summoned, and close to the road to Portsmouth will have served them well.

In 1828, Hallowell inherited the Carew Estate in Beddington from the will of his cousin, Mrs Ann Paston Gee. From then until his death in 1834, aged 73, Admiral Sir Benjamin Hallowell Carew, as he came to be known, lived in his new mansion, taking on the Carew name. He was buried in the crypt of St Mary’s, Beddington.

Hallowell added another piece to the story of Americans who ended up in Croydon in the late 18th and early 19th Centuries. Copley, who painted his parents’ portraits, was buried in Croydon, as was Thomas Hutchinson, the Governor of Massachusetts, whose house was burned down the same night as the mob attacked the Hallowells. Rev East Apthorpe became the vicar of Croydon.

Perhaps Hallowell came to the old Croydon parish church to pay his respects at Hutchinson’s tomb and that of Singleton Copley. He might have looked back with sorrow at what might have been in Boston, but he must certainly have been thankful for the good fortune that brought him an English country estate and a knighthood.

I wonder who made Hallowell’s coffin?