That was the writer that was: Addiscombe Girl Calls the Tunes

Written by David Morgan and published by Inside Croydon on 15 September 2024

Fairfield Halls has hosted an incredible variety of shows over the years. Touring theatre companies would regularly use the venue for a week or two’s performances, as they travelled the length and breadth of the country. In June 1978, theatre-goers headed to the Ashcroft Theatre to see Hayley Mills in a new play titled Hush and Hide. Billed as a comedy-thriller, the story was based on the novel Dear Laura: A Victorian Mystery by Jean Stubbs.

The writers who adapted the work for the stage were Ned Sherrin and Caryl Brahms. Sherrin remains well-known for his theatrical work and for his television and radio programmes. Perhaps he is best remembered for devising, producing and directing That Was The Week That Was, the often controversial satirical weekly review of the early 1960s, which featured David Frost, Willie Rushton, Millicent Martin and Bernard Levin. Sherrin oversaw a team of scriptwriters who included no less than John Cleese, Peter Cook, Roald Dahl, Richard Ingrams, Gerald Kaufman, Frank Muir, David Nobbs, Denis Norden, Dennis Potter, Eric Sykes, Kenneth Tynan and Keith Waterhouse. And Caryl Brahms.

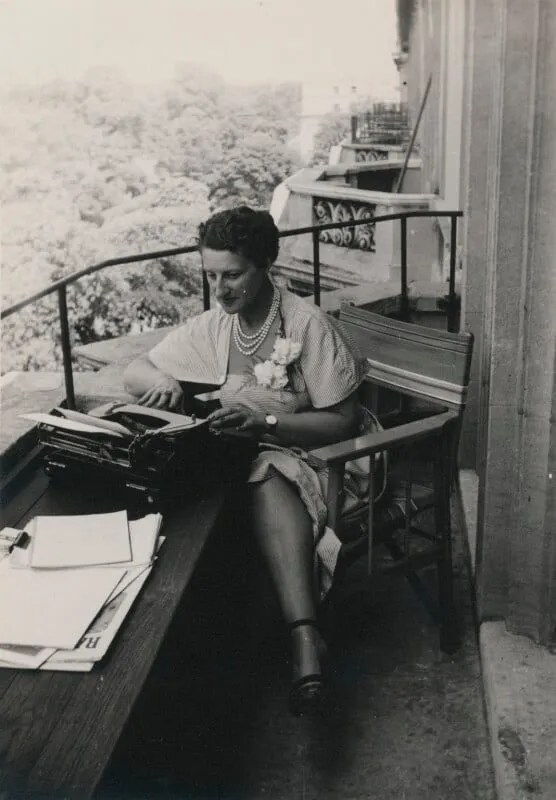

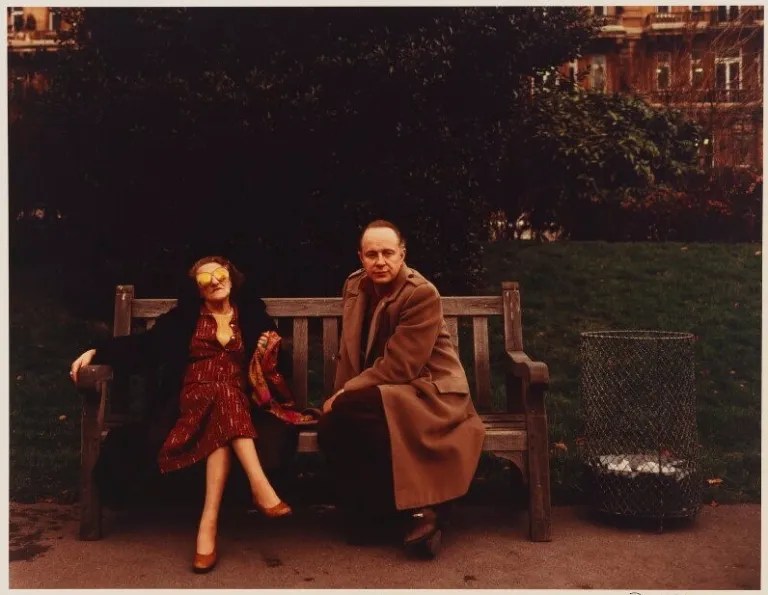

Brahms was a regular collaborator with Sherrin (pictured together below) , and one of the best writers and wordsmiths to come out of Croydon in the 20th Century. Her career as a writer, a novelist and a critic brought her worldwide fame, winning a Novello award in 1965, but she has faded from public recognition since her death. She is another who is unmentioned, forgotten, ignored by Croydon Council’s musical heritage trail…

She was born Doris Caroline Abrahams on December 8, 1901 at 28 Morland Road in Addiscombe. She was an only child. Her father, Henry, was a prosperous wholesale jeweller. Her mother, Pearl, came from a family of Sephardic Jews who had settled in this country a generation earlier. Pearl was one of 21 children. The Abrahams had family connections in Canvey Island and spent many happy summer holidays there.

Brahms’ formal education was at Minerva College in Leicester, the first Jewish boarding school in the country. She then went on to the Royal Academy of Music. Her musical education didn’t go to plan though, as Brahms never finished her course. She decided that her piano playing wasn’t up to the standard that was required, and left. While she was at the Royal Academy, though, Brahms discovered her ability with words. She wrote some verse for the student magazine which the Evening Standard noticed and printed. This was the first time that the name “Caryl Brahms” appeared in print. Young Doris didn’t want her parents to discover what she was up to.

In 1926, David Low began to draw a series of satirical cartoons for the Standard featuring a small dog named “Mussolini”. After protests from the Italian Embassy over the disrespect for the Fascist dictator El Duce, Low continued with his drawings, but shortened the dog’s name to “Musso”. Brahms was hired to write short stories to go with Low’s cartoons. She recruited a partner to help write these pieces, SJ Simon. Simon’s real name was Simon Jackovitch Skidelsky; Brahms always called him “Skid”.

He had been born in Manchuria in 1904, the son of Russian Jews who emigrated to France after the Russian Revolution. He was a top-class bridge player who won many tournaments and who wrote books on the subject. He was the bridge correspondent of The Observer, Punch and the Evening News (this in an age when London had three evening papers, published six days a week).

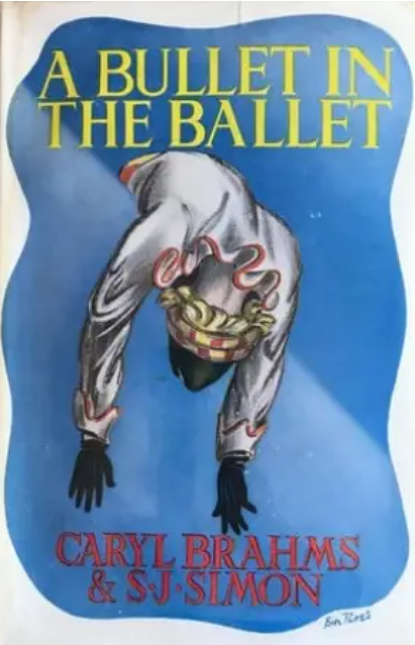

Simon and Brahms shared a quirky sense of humour and brought their individual writing skills to the partnership. In 1937 they wrote their first detective novel A Bullet in the Ballet. Brahms, it was said, wrote the musical, ballet bits and Simon the detecting parts. It was a best-seller and was the first of a series of comic detective novels in which Detective Inspector Quill proved to be more defective than detective. Other novels the duo wrote included Six Curtains for Strogonova, Casino for Sale and Envoy on Excursion.

By 1940, the world was at war. Brahms and Simon published the first of their “backstairs history” books. They were comic retellings of history but with plenty of artistic licence. Don’t Mr Disraeli was a sort of Victorian Romeo and Juliet saga. The follow-up went back to Elizabethan England for No Bed for Bacon, in which the plot involved a young woman who disguised as a boy in order to gain entry to William Shakespeare’s theatrical company. This was a precursor of the plot for the Oscar-winning Shakespeare in Love. In fact, several of Brahms and Simon’s novels were made into films. The Ghosts of Berkeley Square, starring Robert Morley, was released in 1947 and was based on their novel No Nightingales.Trottie True, a novel set in the Edwardian music halls and published in 1946, was turned into a film with the same title in 1949, starring Jean Kent. The writers were putting together another historical review, from the death of Queen Victoria to the death of George V, when Simon died in 1948. Brahms finished the book, You Were There, on her own (both are credited for it). Brahms continued writing. A Seat at the Ballet, a guide for newcomers, came out in 1951, and a novel, Away Went Polly, a year later.

A letter which Brahms received in 1953 was to change her creative output for the rest of her life. It was from a young Ned Sherrin, asking if he could adapt No Bed for Bacon into a stage musical. At first, Brahms told Sherrin that she was not really interested, but he persisted and eventually she agreed to collaborate over the script. It was the beginning of a prolific 20-year writing partnership. Although the reviews for the musical, which was first produced in Bristol, were very good, it wasn’t a financial success. The plot, though, clearly had some lasting qualities with those who saw or heard it, and it was turned into an afternoon drama on BBC Radio 4.

When Sherrin, in his 20s, was appointed as a producer by the BBC, he turned to Brahms to work with him in a variety of comic and satirical productions. That Was The Week That Was, or “TW3”, began its all-too-brief runs in 1962, launching the TV career of David Frost.

Brahms must have chuckled to hear Millicent Martin sing the theme song with lyrics which the writer changed each week to reflect the news headlines. It was Brahms’ work on the sequel to TW3, Not So Much a Programme, More A Way of Life, which won her an Ivor Novello award for the year’s outstanding theme from radio, together with her collaborator Sherrin and the composer Ron Grainer.

Sherrin and Brahms wrote an amazing amount of material together. A novel, Benbow was his Name, about a naval action in the West Indies in 1702, was turned into a film by the BBC, starring Denis Quilley. They wrote a play, Beecham, in 1980 about the Proms conductor Sir Thomas Beecham, which played at the Apollo Theatre, Shaftsbury Avenue, with Timothy West in the leading role.

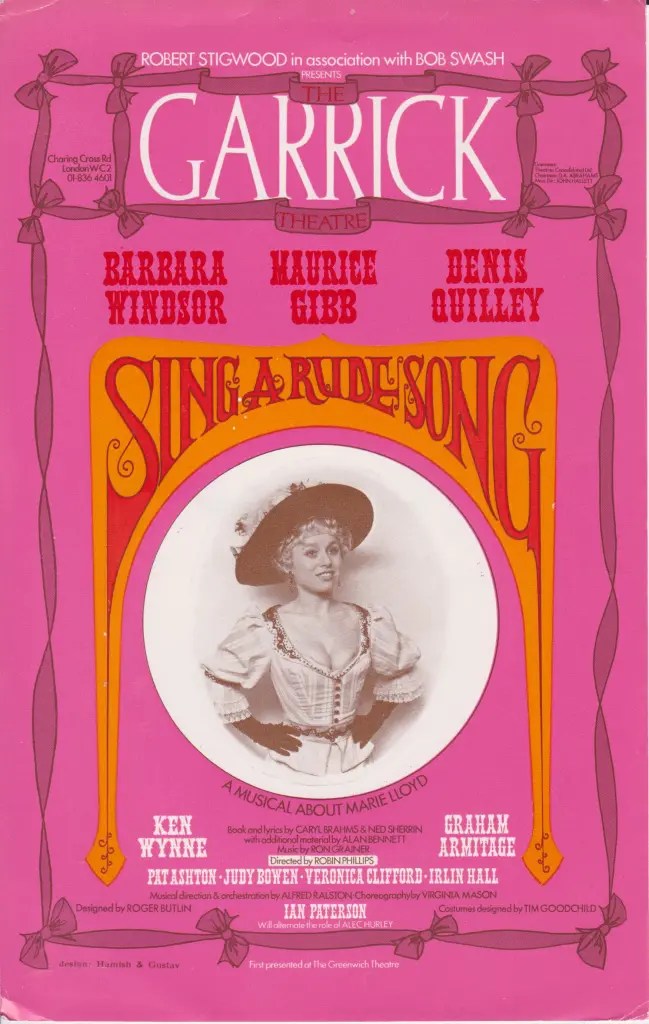

Brahms and Sherrin were to work again with composer Ron Grainer – the man who wrote the theme tune for Doctor Who – on Sing a Rude Song, about the life of the music hall entertainer Marie Lloyd. It starred Barbara Windsor, with Maurice Gibb, of the Bee Gees, in a rare stage role. From 1974 until her death, Brahms was a member of the board of the National Theatre – by then based in its brutalist, purpose-built home on the South Bank.

Brahms worked on one last collaboration with Sherrin, creating a musical The Mitford Girls, “Devised for six beautiful actress singers”, the original production was nominated for two 1981 Society of West End Theatre Awards, including one for Patricia Hodge as Actress of the Year in a Musical. Brahms died in her flat in Regents Park in 1982. Described by Sherrin as “an intimidating woman with a large nose and even larger spectacles”, Brahms was a woman of great ability whose sense of fun and humour brought such a vital dynamic in her works with SJ Simon and Sherrin.

The Jewish girl from Croydon made audiences and readers laugh and cry for half a century, using her power with words to create a special 20th Century niche for herself. In her younger days she loved the ballet and was the dance critic for The Daily Telegraph. She also wrote about ballet and opera for Time and Tide magazine. Taking a great interest in the theatre later in her life she was an inveterate first-nighter, enjoying the glitz and buzz that the opening of a new show brought.

A memoir of Caryl Brahms’s life, put together with much affection by Sherrin, Too Dirty for the Windmill, remains available today, with a decent search of the internet.